Foundations of economic evaluation

Learning Objectives and Outline

Learning Objectives

Identify theoretical and methodological differences between different economic evaluation techniques.

Understand the concepts of summary measures of health, including quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

Be familiar with the steps of valuing costs in economic evaluations.

Outline

Introduction to Economic Evaluations

Types of Economic Evaluations

Who Uses Economic Evaluations

Valuing Health Outcomes

QALYs

DALYs

Valuing Costs

Introduction to Economic Evaluations

Economic Evaluation

Relevant when decision alternatives have different costs and health consequences.

We want to measure the relative value of one strategy in comparison to others.

This can help us make resource allocation decisions in the face of constraints (e.g., budget).

Features of Economic Evaluation

- Systematic quantification of costs and consequences.

- Comparative analysis of alternative courses of action.

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/Valuation of costs both alternative | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

Source: (Drummond et al. 2015)

Cost analysis

Only looks at healthcare costs

Relevant when alternative options are equally effective (provide equal benefits)

- Rarely the case in reality!

Costs are valued in monetary terms (e.g., U.S. dollars)

Decision criterion: often to minimize cost

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/Valuation of costs both alternative | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | Monetary units | Single effect of interest, common to both alternatives, but achieved to different degrees. | Natural units (e.g., life-years gained, disability days saved, points of blood pressure reduction, etc.) |

Source: (Drummond et al. 2015)

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)

Most useful when decision makers consider multiple options within a budget, and the relevant outcome is common across strategies

- Costs are valued in monetary terms ($)

- Benefits are valued in terms of clinical outcomes (e.g., cases prevented or cured, lives saved, years of life gained, quality-adjusted life years gained)

- Results often reported as a cost-effectiveness ratio

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Suppose we are interested in the prolongation of life after an intervention.

Outcome of interest: life-years gained.

The outcome is common to alternative strategies; they differ only in the magnitude of life-years gained.

We can report results in terms of $/Life-years gained

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/Valuation of costs both alternative | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | Monetary units | Single effect of interest, common to both alternatives, but achieved to different degrees. | Natural units (e.g., life-years gained, disability days saved, points of blood pressure reduction, etc.) |

| Cost-utility analysis | Monetary units | Single or multiple effects, not necessarily common to both alternatives. | Healthy years (typically measured as quality-adjusted life-years) |

Source: (Drummond et al. 2015)

Cost-Utility Analysis

- Essentially a variant of cost-effectiveness analysis.

- Major feature: use of generic measure of health.

- Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY): A metric that reflects both changes in life expectancy and quality of life (pain, function, or both).

- By far the most widely published form of economic evaluation.

We will focus mostly on CEA (especially CUA) throughout the workshop

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/Valuation of costs both alternative | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | Monetary units | Single effect of interest, common to both alternatives, but achieved to different degrees. | Natural units (e.g., life-years gained, disability days saved, points of blood pressure reduction, etc.) |

| Cost-utility analysis | Monetary units | Single or multiple effects, not necessarily common to both alternatives. | Healthy years (typically measured as quality-adjusted life-years) |

| Cost-benefit analysis | Monetary units | Single or multiple effects, not necessarily common to both alternatives | Monetary units |

Cost-Benefit Analysis

- Also known as Benefit-Cost Analysis

- Relevant for resource allocation between health care and other areas (e.g., education)

- Costs and health consequences are valued in monetary terms (e.g., U.S. dollars)

- Valuation of health consequences in monetary terms ($) is obtained by estimating individuals willingness to pay for life saving or health improving interventions.

- e.g.: US estimate of value per statistical life ~$9 million

- Cost-benefit criterion: the benefits of a program > its costs

- Notice that we’re not making comparisons across strategies–only comparisons of costs and benefits for the same strategy

- To read more: Robinson et al, 2019

Cost-Benefit Analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28183740/

Cost-Benefit Analysis

https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S2194588818000271/type/journal_article

Who uses economic evaluations?

Health Technology Advisory Committees

PBAC (Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in Australia)

Canada’s Drug and Health Technology Agency

NICE (The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK)

Brazil’s health technology assessment institute

Groups developing clinical guidelines

WHO

CDC

Disease-specific organizations: American Cancer Society; American Heart Association; European Stroke Organisation

Regulatory agencies:

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

CEAs: Identifying Alternatives

Identifying Alternatives

Decision modeling / economic evaluation requires identifying strategies or alternative courses of action.

These alternatives could include different therapies / policies / technologies.

Or, our alternatives could capture different combinations or sequences of treatment (e.g., what dose? what age to start?)

Once we have identified the alternatives, we’ll want to quantify their associated consequences in terms of:

Health outcomes

Costs

CEA components

\[ \frac{\text{(Cost Intervention A - Cost Intervention B)}}{\text{(Benefit A - Benefit B)}}\]

Valuing Health Outcomes

Why summary measures of health?

QALYs and DALYs both provide a summary measure of health

Allow comparison of health attainment / disease burden

Across diseases

Across populations

Over time etc.

QALYs

Origin story: welfare economics

- Utility = holistic measure of satisfaction or wellbeing

With QALYs, two dimensions of interest:

length of life (measured in life-years)

quality of life (measured by utility weight, usually between 0 and 1)

QALYs

QALY: A metric that reflects both changes in life expectancy and quality of life (pain, function, or both)

1 = perfect health; 0= death; Sum of weight*duration of life = quality-adjusted life expectancy

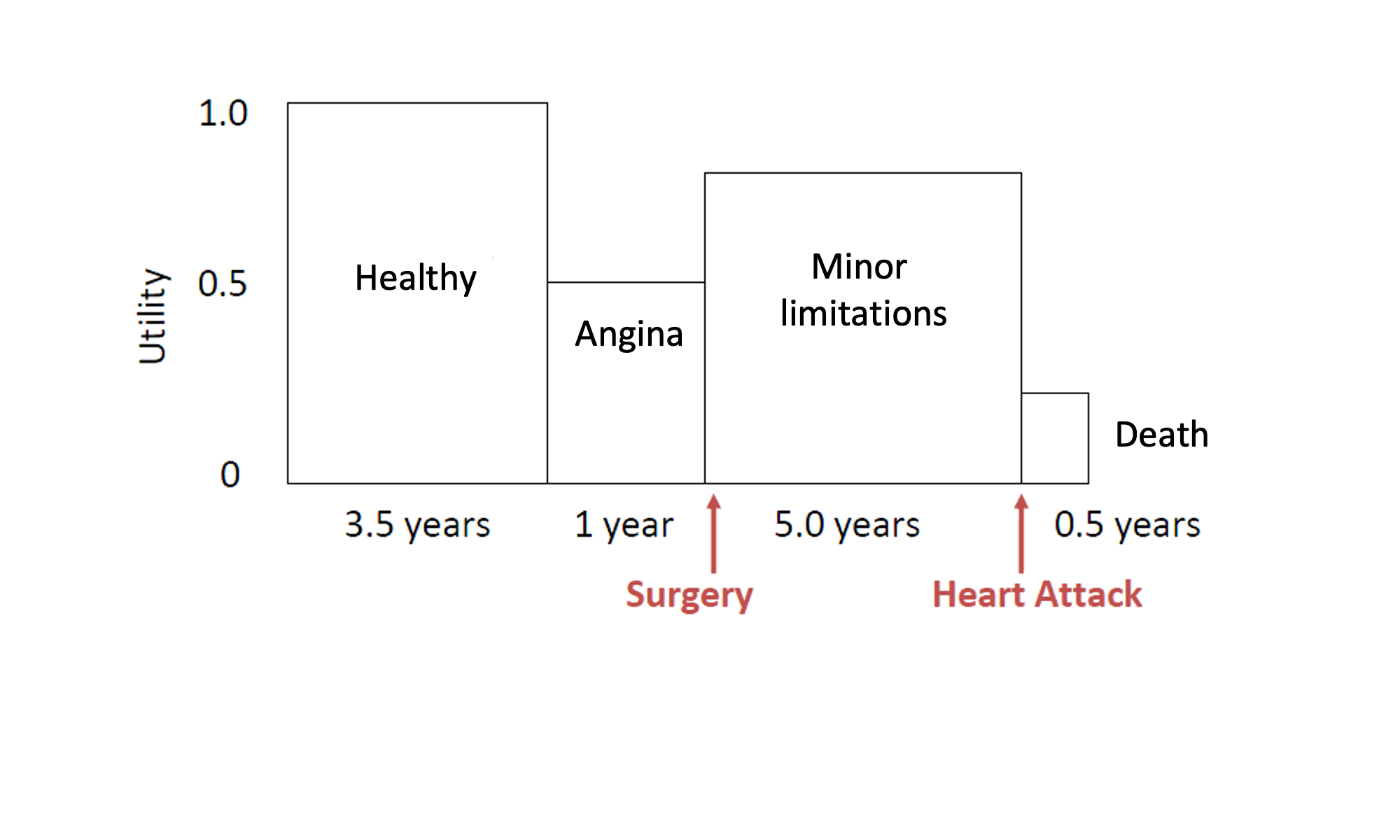

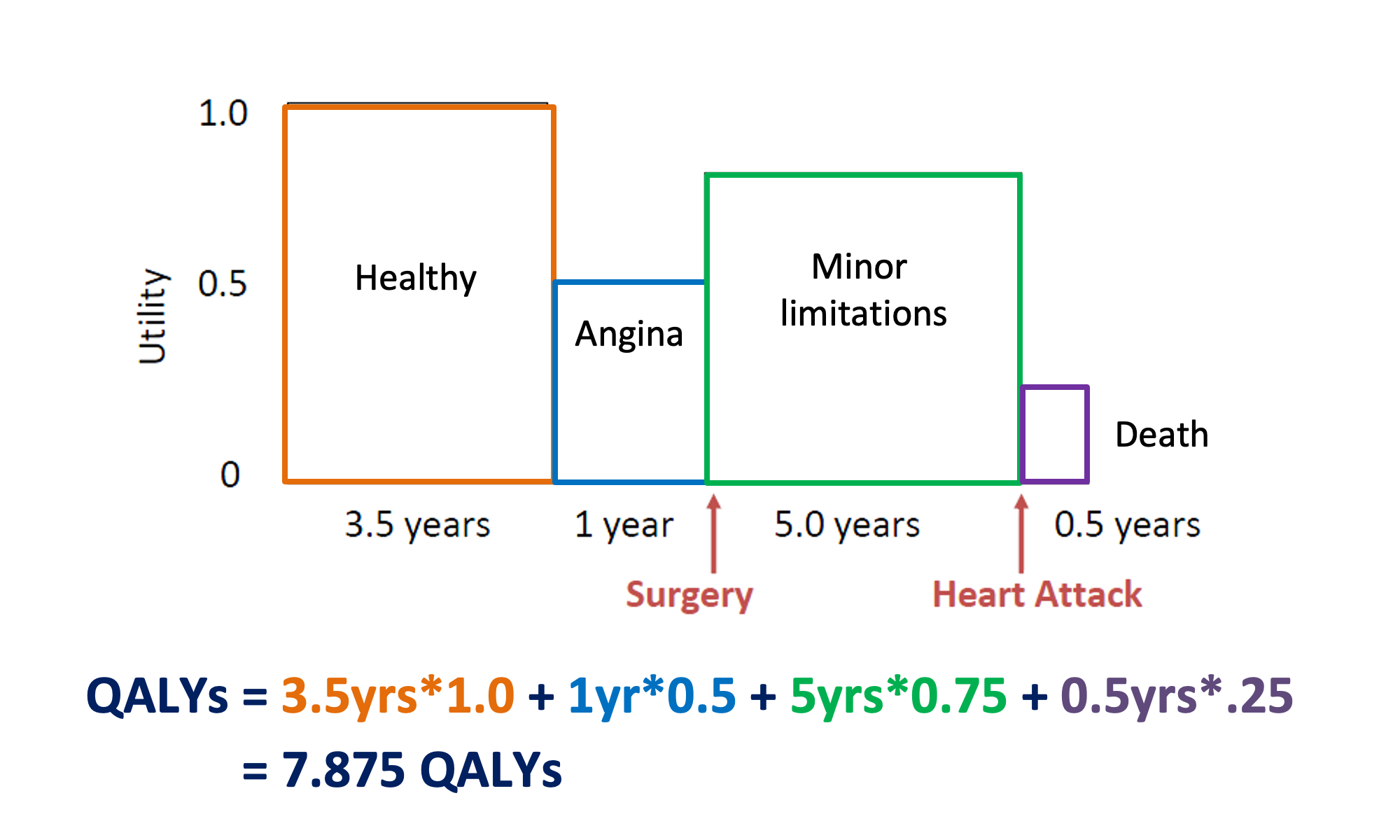

Example: Patient with coronary heart disease (with surgery)

Example: Patient with coronary heart disease (with surgery)

Example: Patient with coronary heart disease (without surgery)

Example: Patient with coronary heart disease

- With surgery: 7.875 QALYs

- Without surgery: 6.625 QALYs

- Benefit from surgery intervention:

In QALYs: 7.875 – 6.625 QALYs = 1.25 QALYs

In life years: 10 years – 10 years = 0 LYs

Utility weights – How are they obtained?

Utility weights for most health states are between 0 (death) and 1 (perfect health)

Direct methods

Standard gamble

Time trade-Off

Rating scales

Indirect methods:

EQ-5D

Other utility instrument: SF-36; Health Utilities Index (HUI)

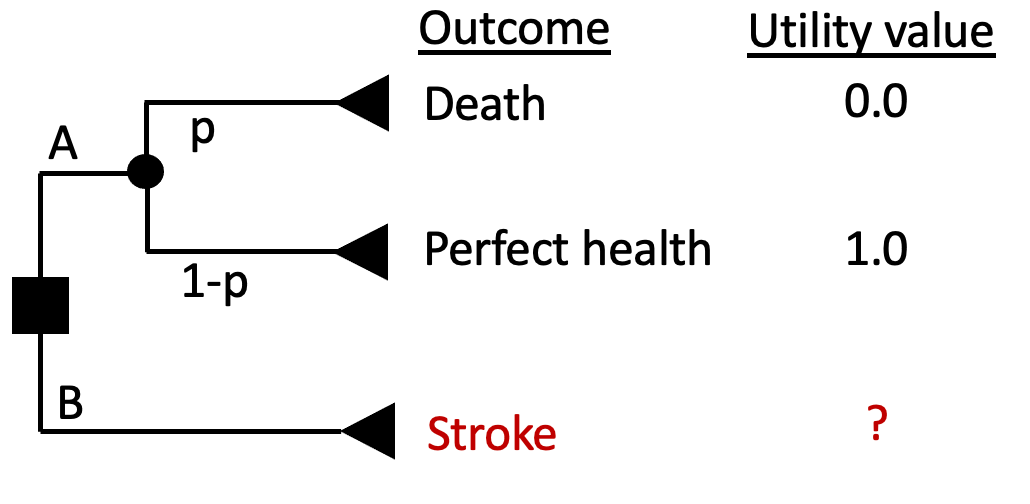

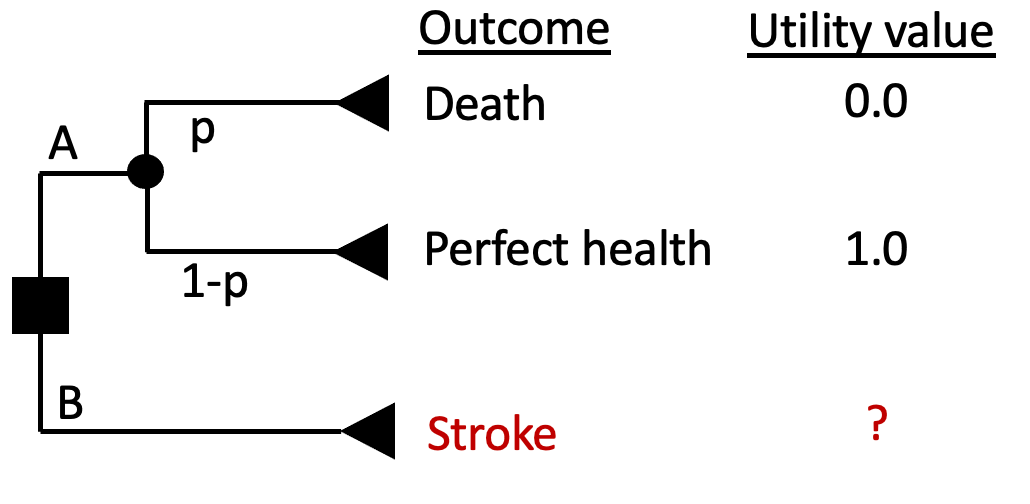

Direct methods - Standard Gamble (SG)

“What risk of death you would accept in order to avoid [living with stroke the rest of your life] and live the rest of your life in perfect health?”

How bad is having a stroke?

As a result of a stroke, you

Have impaired use of your left arm and leg

Need some help bathing and dressing

Need a cane or other device to walk

Experience mild pain a few days per week

Are able to work, with some modifications

Need assistance with shopping, household chores, errands

Feel anxious and depressed sometimes

Direct methods - Standard Gamble (SG)

“What risk of death you would accept in order to avoid [living with stroke the rest of your life] and live the rest of your life in perfect health?”

- Find the threshold \(p_T\) that sets EV(A) = EV(B)

- Assume respondent answered that they would be indifferent between A and B at a threshold \(p_T = 0.2\)

- Then U(Stroke) = \(p_T\)*U(Death) + \((1-p_T)\)*U(Perfect Health) = 0.2*0 + (1-0.2)*1 = 0.8

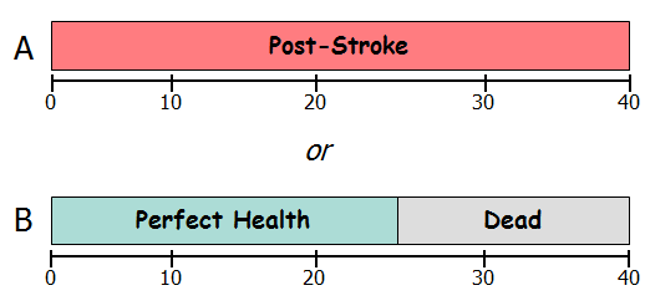

Direct Methods - Time Trade-Off (TTO)

An alternative to standard gamble

Instead of risk of death, TTO uses time alive to value health states

Does not involve uncertainty in choices

Task might be easier for some respondents compared to standard gamble

Direct Methods - Time Trade-Off (TTO)

“What portion of your current life expectancy of 40 years would you give up to improve your current health state (stroke) to ‘perfect health’?”

U(Post-Stroke) * 40 years = U(Perfect Health) * 25 years + U(Dead) * 15 years

U(Post-Stroke) * 40 years = 1 * 25 years + 0 * 15 years

U(Post-Stroke) = 25/40 = 0.625

SG vs TTO

SG represents decision-making under uncertainty; TTO is decision-making under certainty

TTO might inadvertently capture time preference (i.e., we might value health in the future less than we do today) as opposed to only valuing the health states

Risk posture is captured in SG (risk aversion for death) but not in TTO

Utility values from SG usually > TTO for same state

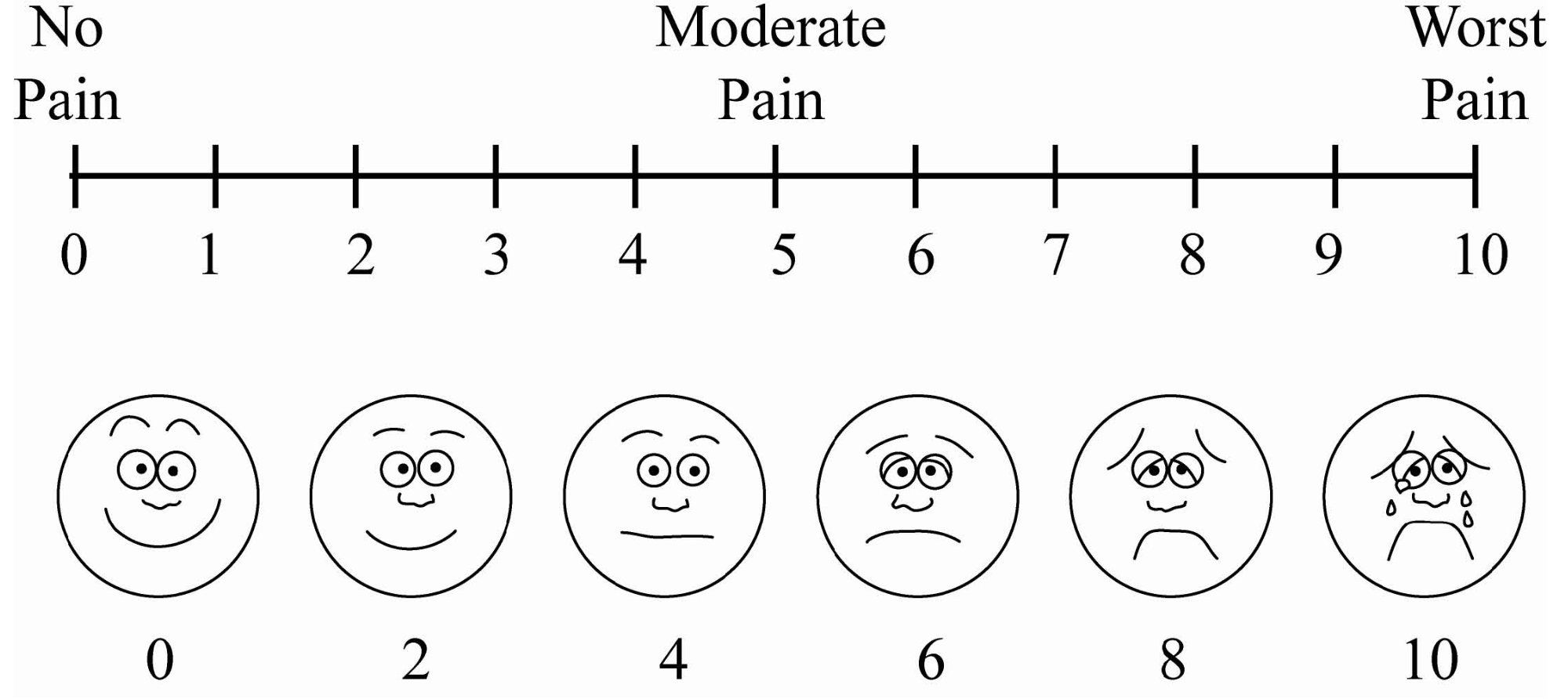

Direct methods – Rating scales

“On a scale where 0 represents death and 100 represents perfect health, what number would you say best describes your health state over the past 2 weeks?”

- Problem: It does not have the interval property we desire

- A value of “90” on this scale is not necessarily twice as good as a value of “45”

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is a commonly-used rating scale

Direct methods – Rating scales

- Easy to use: Rating scales often used where time or cognitive ability/literacy prevents use of other methods

- Very subjective and prone to more extreme answers! Usually, utilities for VAS < TTO < SG

Practical issue – keep an eye out for “cheaters”

Hypothetical “cheating” example:

Drug company X has discovered a drug that prevents diabetes but causes migraines (side-effect)

They use VAS to estimate the utility of diabetes in their decision model and SG to estimate the utility of migraines

Is there a problem here? (yes, there is!!)

Recall, usually utilities for VAS < TTO < SG

Thus, this approach overstates the benefit by using a lower U(Diabetes) and higher U(migraines)

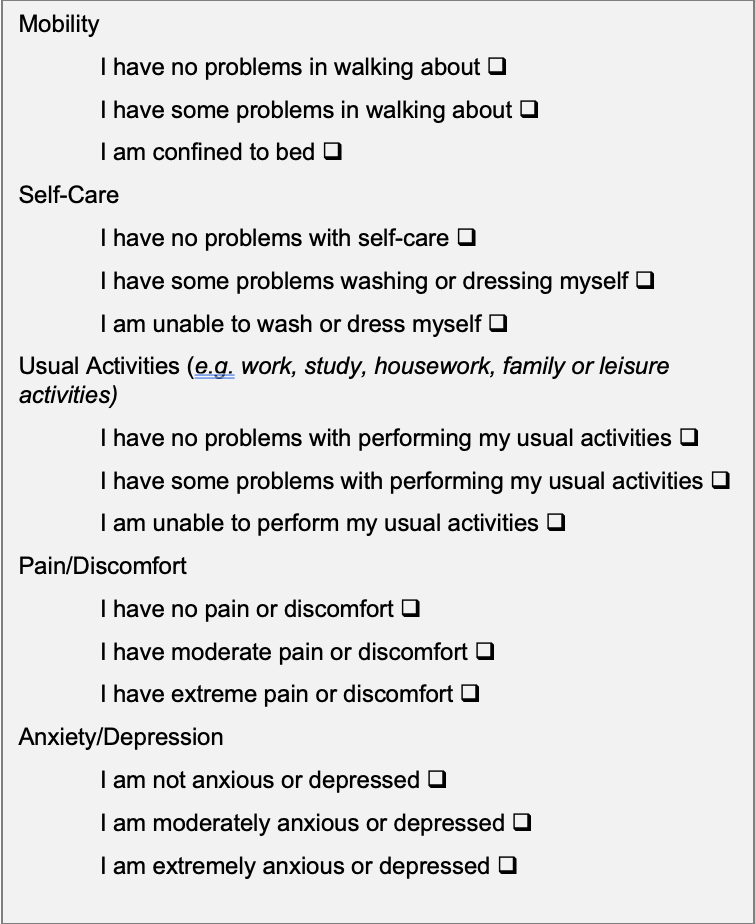

Indirect Methods - EQ-5D

System for describing health states

5 domains: mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain/discomfort; and anxiety/depression

3 levels: 243 distinct health states (e.g. 11223)

Valuations elicited through population based surveys with VAS, TTO

System for describing health states

5 domains: mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain/discomfort; and anxiety/depression

3 levels: 243 distinct health states (e.g. 11223)

Valuations elicited through population based surveys with VAS, TTO

Off-the-shelf numbers for your own CEAs?

- Large scale utility studies

- Balancing tradeoffs between different measures

- Sensitivity analyses!

- Tufts CEA registry

- Alongside RCTs

DALYs

QALY: “0” = death; “1” = perfect health

DALY: “0” = perfect health; “1” = death

- QALY measures the number of healthy years gained (uses preference-based utility weights)

- DALY measures the number of healthy years lost (uses standardized disability weights)

Source: ghcearegistry.org

DALYs

A measure of population ill-health based on “years of life lost” due to premature mortality (Anand & Reddy LSE 2019).

Origin story: Global Burden of Disease Study

Deliberately a measure of health, not welfare/utility

Similar to QALYs, two dimensions of interest:

length of life (differences in life expectancy)

quality of life (measured by disability weight)

DALYs

DALYs = YLL + YLD

- YLL (Years of Life Lost): The # of life years a person could have expected to live had they not died

- YLD (Years Lived with Disability)

DALYs = YLL + YLD

Years of Life Lost (YLL): changes in life expectancy; time lost due to premature mortality

Different approaches to identifying the time lost due to premature mortality:

Age specific risks of mortality; maximum length of life observed in modern world: “synthetic life table”; irrespective of country; socioeconomic characterstics/etc. where death occurs

Dependent on a person’s country of residence & other factors in which the death occurs

Approach depends on purpose of study

- Synthetic life table: Quantify disease burden across countries in relation to normative benchmark and/or in light of global justice and resource re-allocation to low-income countries

- Country-specific life table: Assessing alternative disease interventions in Uganda; how many expected years of life are lost due to a disease in conditions specific to Uganda.

DALYs = YLL + YLD

Example: Calculated from synthetic life table

YLL example: Providing HIV treatment delays death from age 30 to age 50

Life years gained = 20 years

YLL?

Synthetic, Reference Life Table

| Age | Life Expectancy | Age | Life Expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 88.9 | 50 | 39.6 |

| 1 | 88.0 | 55 | 34.9 |

| 5 | 84.0 | 60 | 30.3 |

| 10 | 79.0 | 65 | 25.7 |

| 15 | 74.1 | 70 | 21.3 |

| 20 | 69.1 | 75 | 17.1 |

| 25 | 64.1 | 80 | 13.2 |

| 30 | 59.2 | 85 | 10.0 |

| 35 | 54.3 | 90 | 7.6 |

| 40 | 49.3 | 95 | 5.9 |

| 45 | 44.4 |

Source: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-burden-disease-study-2019-gbd-2019-reference-life-table

Synthetic, Reference Life Table

| Age | Life Expectancy | Age | Life Expectancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 88.9 | 50 | 39.6 |

| 1 | 88.0 | 55 | 34.9 |

| 5 | 84.0 | 60 | 30.3 |

| 10 | 79.0 | 65 | 25.7 |

| 15 | 74.1 | 70 | 21.3 |

| 20 | 69.1 | 75 | 17.1 |

| 25 | 64.1 | 80 | 13.2 |

| 30 | 59.2 | 85 | 10.0 |

| 35 | 54.3 | 90 | 7.6 |

| 40 | 49.3 | 95 | 5.9 |

| 45 | 44.4 |

Source: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-burden-disease-study-2019-gbd-2019-reference-life-table

DALYs = YLL + YLD

Years of Life Lost (YLL): changes in life expectancy, calculated from comparison to synthetic life table

YLL example: Providing HIV treatment delays death from age 30 to age 50

Life years (LYs) gained: 20 years

YLL: LE(50) - LE(30) = 39.6 - 59.2 = -19.6 DALYs = 19.6 DALYs averted

Note

YLL (measured as DALYs averted) \(\neq\) LYs gained!

DALYs = YLL + YLD

Years Lived with Disability (YLD): calculated similar to QALYs, utility weight ≈ 1 - disability weight

YLD example: Effective asthma control for 10 years

Disability weight (uncontrolled asthma) = ?

Disability weight (controlled asthma) = ?

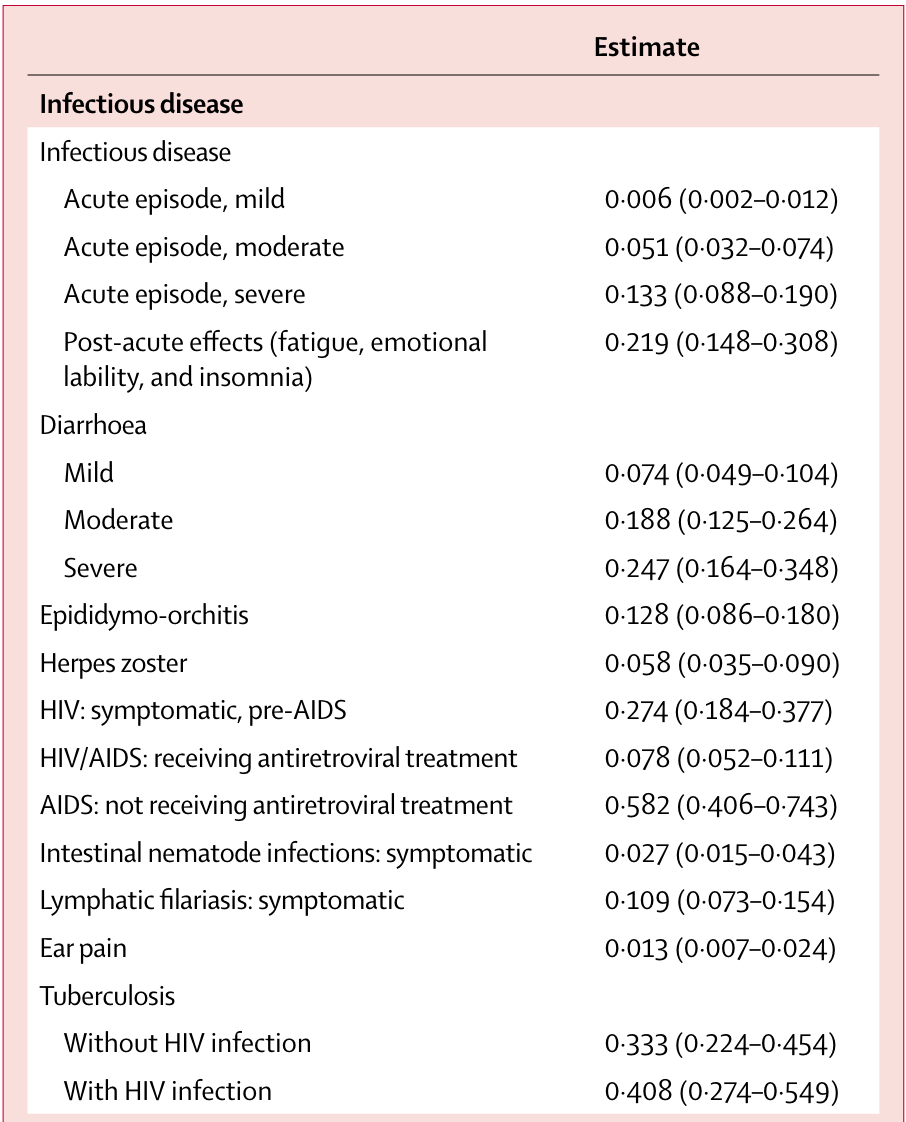

Disability Weights

- Common values for small set of named health conditions (e.g. early/late HIV, HIV/ART)

- First iteration: expert opinion

- Second iteration: Pop-based HH surveys in several world regions (13,902 respondents)

Paired comparison of two health state descriptions which worse

Probit regression to calculate disability weights

235 unique health states

DALYs = YLL + YLD

Years Lived with Disability (YLD): calculated similar to QALYs, utility weight ≈ 1 - disability weight

YLD example: Effective asthma control for 10 years

Disability weight (uncontrolled asthma) = 0.133

Disability weight (controlled asthma) = 0.015

YLD = 10 * 0.015 - 10 * 0.133 = -1.18 DALYs = 1.18 DALYs averted

DALYs for CEA

- Recommended calculation approach has changed over time (age weighting, discounting, now both out)

- Some will calculate a “QALY-like” DALY, using utility weight = 1- disability weight

- Discounting still generally done for CEA (will be covered in Lecture 7!)

Important

Common practice

- High-income setting: QALYs

- Low- and middle- income setting = DALYs***Since disability weights are freely & publicly available (these weights are required for DALY calculations), it can reduce costs/time/resources compared to collecting QALY estimates

Valuing Costs

Steps

Identify

Measure

Value

We can identify different types of healthcare costs

Direct Health Care Costs

Hospital, office, home, facilities

Medications, procedures, tests, professional fees

Direct Non-Health Care Costs

- Childcare, transportation costs

Time Costs

- Patient time receiving care, opportunity cost of time

Productivity costs (‘indirect costs’)

impaired ability to work due to morbidity?

lost economic productivity due to death?

friction costs

We can measure costs using different approaches

Micro-costing (bottom-up)

- Measure all resources used by individual patients, then assign the unit cost for each type of resource consumed to calculate the total cost

Gross-costing (top-down)

- Estimate cost for a given volume of patients by dividing the total cost by the volume of service use

Ingredients-based approach (P x Q x C)

Probability of occurrence (P)

Quantity (Q)

Unit costs (C)

Adjustments needed for Valuing Costs

Discounting

Adjusting for currency and currency year

Will cover these adjustments in Lecture 7!

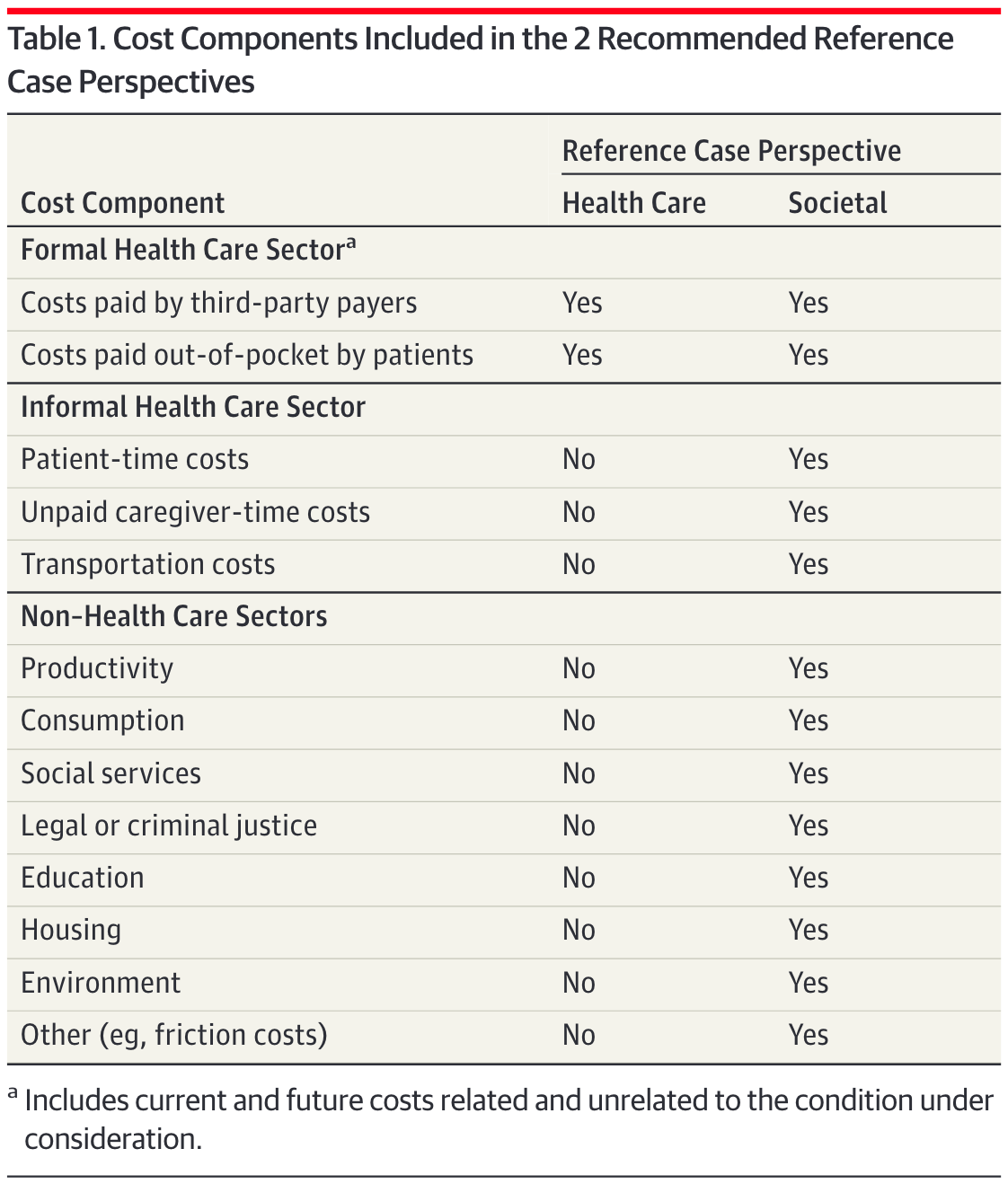

Whose perspective?

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-effectiveness Analyses: Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 2016;316:1093–1103.